Senkaku-Diaoyu Island Dispute – History and Future [PDF]

- Introduction

- History and Claims

- Geological & Cartographic Evidence

- Geographic Formations

- Cartographic Evidence

- Geological & Cartographic Evidence

- Role of International Organizations: United Nations

- World Meteorological Organization

- Conferences on the Law of the Sea

- International Court of Justice (ICJ)

- Theory-Based Interpretation

- Conclusion

- Works Cited

Introduction

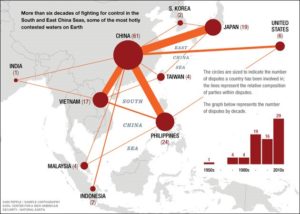

The purpose of this investigation is to assess the historical implications of and potential future outcomes for the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute in the East China Sea between Japan, China (People’s Republic of China) and Taiwan (Republic of China). The focus of the research is on the role of international organizations, particularly the United Nations and affiliated entities, in escalating and supporting resolution of the dispute.

The purpose of this investigation is to assess the historical implications of and potential future outcomes for the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute in the East China Sea between Japan, China (People’s Republic of China) and Taiwan (Republic of China). The focus of the research is on the role of international organizations, particularly the United Nations and affiliated entities, in escalating and supporting resolution of the dispute.

The Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands (herein referred to simply as “the islands”) consist of 5 main island formations with arguable habitability and 3 smaller rocky islets. The Chinese, Japanese and Taiwanese governments have all claimed sovereignty over the islands, with claims reaching back several centuries. China argues that the Ming and Qing Dynasties were first to discover and give name to the islands, inherently making them a part of the Chinese territory. Japan has claimed sovereignty over the islands since the late 1890’s, and according to the United States currently administers the islands – the sovereignty remains in discussion between the nations.

Many scholars documenting the dispute have disregarded the role of Taiwan for simplification purposes, however the question of sovereignty over the islands and the disputed territorial and economic waters require an understanding of Taiwan’s role and stake. This report includes a history of the dispute, a review of each nation’s role in the global and regional energy economy, and how historical factors and production and demand for energy affect each country’s position and stake on the islands and associated waters. In addition, the role of the United States’ in the dispute is examined with respect to its economic relations to both countries, and its obligatory military support for a defensive Japan.

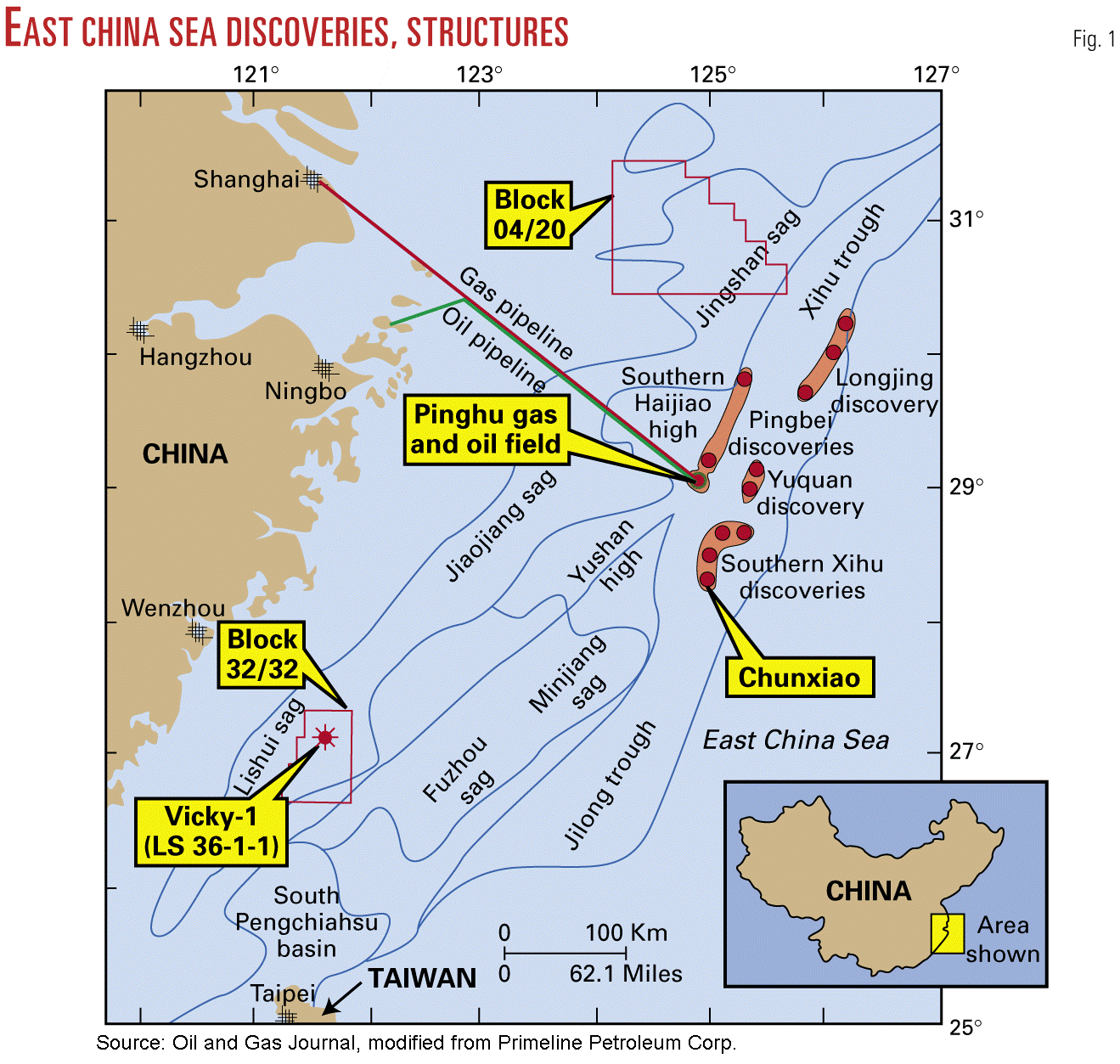

For China, the islands represent a nationalist claim and attempt to enforce their regional power among the Asian nations. Since the Sino-Japanese war of 1894, Chinese nationalists have long harbored resentment towards the nation and people of Japan. The undemocratic state of China has incensed the island dispute both to support nationalism and to detract attention from domestic issues. The economic resources in the East China Sea represent the core function for the area, and China has begun to produce oil and gas from reserves just west of the disputed sea territory. The country is eager to supply their growing demand for hydrocarbon resources, particularly for Shanghai municipality and the Zhejiang province near the East China Sea which are both heavily populated and distant from inland hydrocarbon sources. Exploitation of the East China Sea hydrocarbon resources provides these regions with more easily-accessible energy sources.

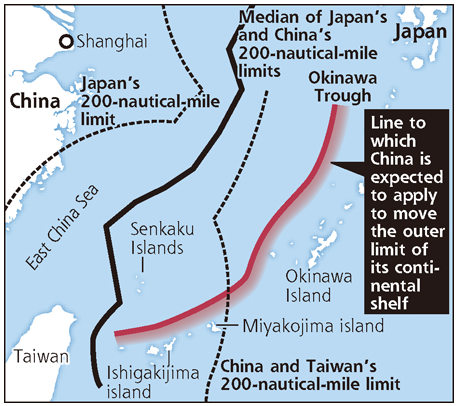

For Japan, the hydrocarbon resources in the East China Sea are theoretically promising, but pose severe technological/engineering challenges. While China can lay underwater infrastructure to easily transport oil and gas to the mainland, Japan’s mainland islands lay further from the hydrocarbon-rich reserves, and are separated by the very deep Okinawa Trough. The transportation of hydrocarbon resources to populous Japanese territories is thus much more difficult than it is for China, leaving Japan to vie for shared development. This path continues to be difficult to initiate, as Taiwan exerts a claim to the islands while China retains its sovereignty claim over Taiwan and refuses its presence in negotiations.

In the dispute over the islands, two issues are at stake: the sovereignty of the islands themselves, and the respective rights of the nations to the continental shelf and territorial sea resources. The United States has no position on whether or not the islands are Japanese sovereign territory, however they affirmed their stance on Japan’s administration over them and the islands’ application to the 1960 US-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security. President Obama paid a visit to Japan in May of 2014 and issued a public statement recognizing that the islands fell under the responsibility of the United States to protect, should they be infiltrated by foreign forces. The US seeks to absolve itself from the conflict over sovereignty, especially as it concerns the fragile relationship between China and Taiwan, and encourage bilateral negotiations and options for adjudication.

The increasingly important political and economic stakes may undermine the settlement process and the role of international law. Additionally, the principals of international law pertaining to exploitation of natural resources adjacent to territorial waters are imprecise, and disputes over conflicting sovereignty claims are difficult to bring to resolution without voluntary settlement or initiative from effected parties. The definition of the continental shelf and associated economic zones with respect to each country’s sovereign territory restricts further development of the area.

The United Nations (UN) has played a critical role in escalating the dispute through its 1968 hydrologic survey revealing large potential for hydrocarbon resources in the region of the East China Sea, however the organization has thus far yielded little progress towards peaceful resolution of the disagreement. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted in 1982 and establishes customary international law for countries territorial waters, exclusive economic zones, and continental shelf. The Convention and the following amendments have given rise to questions of interpretation in particular cases, previously leading to international arbitration. The dispute of sovereignty over Senkaku/Daioyu Islands likely must go to the ICJ for resolution, while the opportunity for joint resource development stands a better chance of achieving bilateral development plans than taking on the battle by physical or judicial means (Shelf, 2013). For this to happen, Japan insists the islands must be recognized as their sovereign territory by China.

The United Nations (UN) has played a critical role in escalating the dispute through its 1968 hydrologic survey revealing large potential for hydrocarbon resources in the region of the East China Sea, however the organization has thus far yielded little progress towards peaceful resolution of the disagreement. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was adopted in 1982 and establishes customary international law for countries territorial waters, exclusive economic zones, and continental shelf. The Convention and the following amendments have given rise to questions of interpretation in particular cases, previously leading to international arbitration. The dispute of sovereignty over Senkaku/Daioyu Islands likely must go to the ICJ for resolution, while the opportunity for joint resource development stands a better chance of achieving bilateral development plans than taking on the battle by physical or judicial means (Shelf, 2013). For this to happen, Japan insists the islands must be recognized as their sovereign territory by China.

History and Claims

China claims sovereignty over the islands, citing their documented during the Ming dynasty era as early as 1403 through their inclusion in maps and surveys, whereas Japan’s first claim over the islands likely occurred only in the late 19th century. In the 1160’s the Ryukyu Islands became involved with Japan after the birth of the first King of Okinawa, an exiled Japanese nobleman (Agency, 1971). The Ryukyu Islands were officially claimed by Japan in the late 12th century with the establishment of the Satsuma Province, which saw the incorporation of the Kyushu Island and associated southern islands. During the 14th century and the Ming dynasty, a Chinese community was established in the city of Naha, Okinawa. In 1572, Okinawa-raised students were sent to Kyoto for the first time to continue their studies.

Shortly after 1603 and the Tokugawa Shogunate’s rise to power, Okinawa was taken by force and incorporated into the Satsuma Province, formally established as a separate Japanese prefecture in 1879. The islands were officially obtained by Japan as a result of the Sino-Japanese war and the subsequent annexation legalized by the Treaty of Shimonoseki in May of 1895. Following the formal acceptance of the Treaty, Japan maintained exclusive supervisory possession of the islands until the US took administrative control after WWII.

For almost a century the dispute over the island territories was of little significance to either Japan or China/Taiwan. The 1943 Cairo Declaration and enforcement through the 1945 Potsdam Declaration required the return of territories seized by Japan after 1914, and did not include the island territories. Instead, the Declarations allowed Japanese sovereignty over the four main islands and “…such minor islands as [the Allied Powers] determine.” (1973). In the 1952 San Francisco Peace Treaty, the United States specifically took administrative control over the islands, while former Secretary of State John Foster Dulles assured that Japan retained residual sovereignty over the islands throughout the US’s control. Neither Taiwan nor China contested the bilateral Peace Treaty agreement signed in 1952.

With the ratification of the Treaty, the United States had the right to exercise powers of administration, legislation and jurisdiction over Japanese islands south of 29° N, including territorial waters. Just 20 months later in December 1953 the United States relinquished the control over all islands north of 27° N, with the Okinawa, Miyako, and Yaeyama islands remaining in the control of the U.S. In June 1957 the United States issued Executive Order 10713, staking administrative claim over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands for bombing purposes. The islands were returned to Japan’s administrative control in 1972 as part of the reversion in Okinawa.

In 1968 the UN conducted a hydrographic survey of the East China Sea which uncovered vast oil reserves in the continental shelf and disputed waters around the islands reignited the dispute over sovereignty of the islands and associated economic zones. Representatives of both Japan and China were aboard the research vessel. Following the discovery of oil, the Japanese Government sponsored a 1969 survey with Tokyo University of the underwater geology around the islands, confirming the presence of sub-seabed oil reserves. In July of 1969, the government of the Republic of China granted a permit to the American-owned Gulf oil firm to explore the continental shelf around the islands, while simultaneously making an informal case that the islands were not part of Japan’s sovereignty based on the San Francisco Peace Treaty that limited Japan’s sovereignty to the four main islands.

Shortly following the 1969 Japanese survey of the oil resources, the Chinese government ratified the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf that dictates the process for resolving continental shelf boundary disputes. The Convention states that the boundary of the continental shelf should be resolved between the disputing states, and without any such agreement in place the boundary shall not be beyond the median line between the territorial waters of the states. China has, however, additionally asserted in their ratification that the continental shelf is a part of the natural prolongation of their land territory and thus remains the jurisdiction of the Chinese government. China included a reservation to the Convention which stated that no exposed rocks or islets can be taken into account when determining the boundary of the continental shelf, further protecting their assertion of sovereignty over the shelf and associated waters.

On July 20, 1970, Taiwan issued a query to the Japanese Embassy in Taipei regarding their interpretation of the Ryukyu Islands, to clarify whether or not it included the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. In response, Japan established a task force to study the international law surrounding the continental shelf and issue a formal policy on behalf of the Japanese Government. In addition, Japanese administrators requested a meeting with Taiwanese administrators in the summer of 1970 to discuss the islands. On August 16th of 1970, Taiwan submitted a resolution claiming title over the islands, their first formal denunciation of Japan’s claim over sovereignty.

Before the two countries came together for a formal meeting, two separate incidents in the early summer intensified the nationalist debate over the islands. A flag for the Republic of China (Taiwan) was posted on one of the islands, along with a sign bearing the slogan “Long Live President Chiang”, then-president of the Republic of China. Officials denied responsibility for the placement of the sign and flag, and both were promptly removed by the Ryukyu Island government. Separately, Taiwanese fishing vessels were ordered to evacuate the waters surrounding the islands by two apparent Japanese naval patrol boats, a claim which the Japanese government similarly denied.

In September of 1970 the Japanese government reaffirmed official claim of sovereignty over the islands, while maintaining that the issue over the continental shelf still required resolution with China and Taiwan. This statement came about the same time at which the government of the Ryukyu Islands submitted a legislative resolution to the Japanese government claiming the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands were part of the Ryukyu Island territories, in addition to supporting the equidistant delineation of the continental shelf based on the Continental Shelf Convention.

A public statement by the government of the Republic of China in February of 1971 claimed sovereignty over the islands by Taiwan, with a private note from the ROC Ambassador in Washington asking the U.S. to “respect the sovereign rights…over Tiao-yu Tai [Diaoyutai] islets and restore them…” to the Republic of China after the U.S. ends its occupation of the Ryukyu Islands (Agency, 1971).

The People’s Republic of China claimed the 12 nautical mile territorial water off the mainland’s cost after the 1958 Geneva Convention, but made no further claims of the continental shelf for the following 12 years until 1970 despite the 1968 survey and discovery of oil resources. When the territorial disputes between the Republic of China and Japan began to simmer, the People’s Republic of China maintained a relative silence over its interpretation of sovereignty over the continental shelf and island territories. In August and September of 1970, however, two communist newspapers out of Hong Kong began to accuse Japan and the Republic of China (Taiwan) of extracting petroleum resources from the East China Sea. Then in December of 1970, A New China News Agency (NCNA) broadcast Chinese claims to the islands as part of the Chinese continental shelf, exacerbated by a subsequent newspaper article claiming the exploitation of oil reserves by Japan were to satisfy the growing needs of its military. Japan interpreted the responses of China as a reminder of its presumed sovereignty over the Republic of China (Taiwan) and the East China Sea continental shelf. Despite the prolonged silence from the Chinese government, these actions were perceived as an intention to fully exploit the resources of the continental shelf area.

The cooperation on the exploration of the resources around the islands and associated waters between Taiwan and Japan furthered China’s fears that strengthened relationships between the two other nations would complicate the ultimate sovereignty settlement between China and Taiwan. In January 1971, the People’ s Republic of China referred for the first time to the Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf, laying the groundwork for a relatively moderate stance on the territorial dispute and potential for negotiations on the apportionment of the sea and shelf territories.

Since the 1970’s, China has been exploring and exploiting the hydrocarbon resources around its side of the median line (as defined by Japan). The Chunxiao gas and oil field is closest to the median line and offers an interesting case study of the dispute. In 2004 international corporations Unocal and Shell oil companies withdrew from the development of the field after just one year of participation, following almost 8 years of negotiations, citing high costs, unclear reserves, and perhaps more significantly the territorial dispute between the two nations. In 2006 China began independently producing the resources through the China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) and a private subsidiary of the government-owned Sinopec Group. Around 2008, China and Japan formalized agreements to pursue joint exploration of resources around the median site, with a distinction between the territorial dispute over the islands and the rights to develop the undersea resources. The joint development plan explicitly avoids the legal claims to the area, simply defining an ‘understanding’ for cooperation in the Chunxiao gas and oil fields. The implementation of the agreement into a binding treaty came to a halt in 2010, and thus far no agreement on the rights and interests for the production have been achieved. Territorial challenges encircle the region, and challenges to islands and seabed resources are being exacerbated.

At present, China maintains the only oil and gas projects in the East China Sea. Husky Oil China, a subsidiary of the Canadian parent company, operates a block of the sea, while 3 other blocks were opened in 2012 and currently await awarding by the Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). The LS 36 field near Taiwan is being explored by the CNOOC and Primeline Petroleum Corp, with planned pipelines to a new processing plant in Wenzhou capable of producing over 40 million ft3 of gas per day and slated for completion in 2017 (SinoShip News, 2013). The CNOOC has in total approximately 9 total fields, only two or three currently producing. The true potential and impact of the fields’ reserves are questionable, and the resources from the East China Sea remain a fraction of the nation’s total production (and even less of the demand). Many argue there are vast resources in further disputed waters near the islands, the true potential of which will not be harnessed without an agreement between the feuding nations (Administration, 2012).

At present, China maintains the only oil and gas projects in the East China Sea. Husky Oil China, a subsidiary of the Canadian parent company, operates a block of the sea, while 3 other blocks were opened in 2012 and currently await awarding by the Chinese National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). The LS 36 field near Taiwan is being explored by the CNOOC and Primeline Petroleum Corp, with planned pipelines to a new processing plant in Wenzhou capable of producing over 40 million ft3 of gas per day and slated for completion in 2017 (SinoShip News, 2013). The CNOOC has in total approximately 9 total fields, only two or three currently producing. The true potential and impact of the fields’ reserves are questionable, and the resources from the East China Sea remain a fraction of the nation’s total production (and even less of the demand). Many argue there are vast resources in further disputed waters near the islands, the true potential of which will not be harnessed without an agreement between the feuding nations (Administration, 2012).

China and Japan have brought evidence and complaints to various international organizations, most notably through the United Nations, its Convention on the Law of the Sea, and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Conflicting claims to the shelf in the ECS have been made by both nations from 2008 to the present, leading to what Japan believes should be an equidistant divide of the sea (with the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands belonging to Japan), and China insists as the natural prolongation of the continental shelf.

Geological & Cartographic Evidence

Geographic Formations

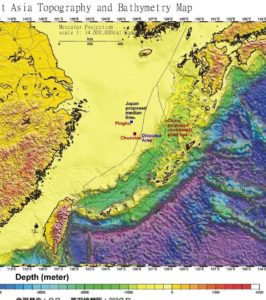

The geology of the islands and surrounding seabed help to define the territory and potential for oil extraction and transportation. The geologic formations are also important features in defining the territorial sea area, economic zones, continental shelf, and applications of international law on such.

A 1969 geological survey by Japan confirmed that the island and islets are on the seaward fringe of the outer continental shelf with varying geological formations (namely consisting of sedimentary rock and fossil-bearing conglomerates) (Agency, 1971). The continental shelf near the islands that contain oil reserves slope into the seabed region referred to as the Taiwan Basin, with water depths between 100-200 meters. The continental shelf ends less than 40 nautical miles east of the islands, where the water depth reaches over 2,500 meters (Agency, 1971). The trench, referred to as the Okinawa Trough, separates the islands and much of the East China Sea from the Ryukyu Islands and mainland Japan, furthering China’s claim that the islands are within the continental shelf and physically detached from the remainder of Japanese territories.

A dilapidated fish processing facility remains the only structure on the largest island (Uotsuri-jima in Japanese), located on the western side of the largest island where the only possible landings for small boats is located. The eastern side of the island falls sharply into the water. Most of the smaller islets are rocky volcanic formations that remain nearly impossible to making landing on.

A dilapidated fish processing facility remains the only structure on the largest island (Uotsuri-jima in Japanese), located on the western side of the largest island where the only possible landings for small boats is located. The eastern side of the island falls sharply into the water. Most of the smaller islets are rocky volcanic formations that remain nearly impossible to making landing on.

The most significant disagreement with respect to the geography of the region pertains to the definition of the continental shelf. Japan argues that the Okinawa Trough is ‘a dent’ in the shelf’s prolongation, whereas China sees the trough and associated depths of water as the end of its shelf extension and thus the rightful end of their claim to the continental shelf.

Cartographic Evidence

The “Red Guard” atlas published in 1966 in Peking includes a map displaying the boundaries of Chinese administrative areas; the sea around the islands are specifically excluded from this administrative area claimed by China, while also showing the Ryukyu Islands as Japanese territory. A following map in the “Red Guard” also separates the ocean and island territories from mainland Taiwan, in contrast to more recent statements suggesting that Taiwan includes “islands appertaining thereto”.

In 1967 the same maps were published in the Atlas of China’s “Popular Edition”, again published in Peking. The deliberate delineation of the islands as “national boundaries”, as opposed to the “unsettled national boundaries”, indicates that China did not contest the sovereignty of the islands prior to the discovery of oil in the region (Agency, 1971). Prior Chinese Nationalist maps fail to specifically indicate the presence or ownership of the islands, including in specific depictions of northern Taiwan which include several islands located about half of the way from mainland Taiwan to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands.

The Chinese Petroleum Corporation (CPC), which coordinates all oil and gas development activities, published a geologic map of China in 1970 which did not depict the islands. The Republic of China’s Ministry of National Defense published an Atlas of China shortly following the CPC map which does indicate the islands with their Chinese name and Japanese name in parenthesis. The previous version of the map in 1962 displayed the islands but did not provide any name for them.

Role of International Organizations: United Nations

World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is an international organization with 191 member states which in 1950 was established as the United Nation’s agency for meteorology, hydrology and geophysical science. The WMO has a Congress which determines the agency’s policies every four years, with a representative from each member nation. The WMO also has an annual executive council which carries out the policies of the Congress, and six regional divisions. The WMO was established to provide a framework for international cooperation in the development and application of meteorology and hydrology practices.

With respect to the dispute of the islands, the WMO recognized that the main island of the Senkaku/Diaoyutai (Uotsuri-jima/Diaoyu Dao) were a part of the Ryukyu Islands, and had been under the administration of Ishigaki Islands prior to World War II. Subsequent to WWII, the US Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands Proclamation #27, Article 1 (based on the San Francisco Peace Treaty), “Geographic Boundaries in the Ryukyu Islands”, specifically placed the Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands in the area of U.S. administration. This distinction provides Japan with support for their claim of undisputed prescriptive sovereignty over the islands.

Conferences on the Law of the Sea

In 1958 the United Nations (UN) concluded the first United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in Geneva, opening for signature four conventions that helped define the territorial seas, high seas, continental shelf and additional maritime laws and processes. The Conference was convened through the UN’s General Assembly resolution 1105 (XI) in February of 1957 after significant international pressure. The basis for the Conference came from the Hague Conference for the Codification of International Law held in the 1930’s under the League of Nations. Attended by 86 nations and following the general protocol of the UN General Assembly (including provisions being adopted to committee with simply majority and requiring two-thirds majority in the plenary), the Convention sought to resolve some international disputes, though the voting procedure made some resolutions impossible (such as the breadth of the territorial sea). UNCLOS is the primary form of international law that provides guiding principles for maritime jurisdiction and rights, while simultaneously creating several questions with respect to the Convention’s application in the East China Sea.

The Convention recognizes that nation states have sovereign rights over the contiguous continental shelf for purposes of exploring and exploiting the natural resources located within them, and defines the continental shelf as “…the seabed and subsoil of the submarine areas adjacent to the coast but outside the area of the territorial sea, to a depth of 200 m, or beyond that limit, to where the depth of the superjacent waters admits of the exploitation of the natural resources of the area…” (1973). This open-ended definition gave rise to further disputes, as the development of new technologies and techniques enabled the exploitation of seabed resources well beyond the 200 m depths defined in the Convention. In the situation of overlapping claims, article 6 of the Convention mandates boundary lines be determined by agreement between the concerned states, and wherein no agreement exists the boundary should be the medial line between the disputing nations. The ambiguous definitions provided in the Convention left inadequate guidelines for resolving conflicting claims, made increasingly difficult when disputing nations were not party to the Convention.

The sovereignty over the islands plays a critical function in the dispute over maritime jurisdiction, if it is accepted that some of the islands in the grouping are capable of sustaining inhabitants and would thus provide grounds for territorial waters and an accompanying EEZ.

Referencing the Convention, China claims a right to the continental shelf and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) extending up to 350 nautical miles east from the coastline into the East China Sea (to the end of the natural prolongation of the continental shelf as defined by China), while Japan has the right to claim an EEZ that extends up to 200 nautical miles to the west from their coastline. While China pursues oil and gas development activities just west of the disputed territories, the two countries have agreed in principal to cooperative development of the resources in the disputed areas. From 2004 to 2008, Japan and China engaged in cabinet-level meetings to discuss joint development of resources in the disputed area, however little tangible progress has been realized away from the theoretical partnership.

If the equidistance approach is used to determine a boundary between the two states, the decision over sovereignty over the islands would determine the control over almost 20,000 square miles (Ramos-Mrosovsky, 2008).

China and Japan have from 2008-2014 presented numerous submissions to the UNCLOS and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf with little progress. In the thirty-second session, the Commission reviewed the presentations and notes from each of the two nations, noting the non-reference to the islands in dispute. Japan has invoked paragraph 5 of annex I to the Rules of Procedure of the Commission which provides that in the case of a disputed maritime border, the Commission shall not consider or qualify submissions made by the states in question unless provided prior consent by each nation. If the Okinawa Tough is proven to be a fundamental discontinuity of the natural prolongation of China and Korea from that of Japan’s as defined by Article 76 of the UNCLOS, the median line which Japan currently claims should not be applied in the continental shelf delimitation.

The submissions to UNCLOS and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf will likely not be considered given the presiding maritime delimitation disputes.

International Court of Justice (ICJ)

The ICJ is the principal judicial body of the United Nations, with the role of settling in accordance with international law any legal disputes submitted to it by the conflicting nations. The Court is comprised of 15 judges who are elected for 9 year terms by the General Assembly and the Security Council. Both Japan and China currently maintain one judge in the Court.

In a case similar to that of the Senkaku/Daioyu Islands, the ICJ in the North Seas Continental Shelf Cases of 1969 set out that the provisions in the Convention were not (yet) considered customary international law and binding on non-signatories due to the fact that the Convention had not become “an inescapable principle of a priori accompaniment of basic continental shelf doctrine” (1973). Instead, the ICJ set out that the principles of law to be applied in resolving disputes over the continental shelf must adhere to three basic equitable principals, namely: the obligation to enter negotiations with the intention of resolving the dispute; taking into account relevant circumstances by all parties electing a settlement; and recognition of the natural prolongation of states’ terrestrial bodies, and the non-infringement upon similar prolongations of other nation states (1973).

Due to the vague nature of the Convention and accords set out by the ICJ following the North Seas cases, the United Nations General Assembly agreed in 1970 to convene a Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1973 to be charged with establishing an international process by which such disputes could be resolved.

The ICJ favors a two-stage approach for resolving maritime jurisdiction disputes based on the UNCLOS. First it defines a provisional equidistant line similar to that defined by the 1958 Convention, and secondly it considers whether special circumstances require equitable adjustment. Settlement of the islands dispute is unlikely to take place through the ICJ as neither Japan nor China are seemingly willing to bring the case to the Court, or to agree to its jurisdiction if the other nation introduces it. China’s vast number of both recognized and unrecognized open territory disputes present a overwhelming incentive to keep the disputed claims out of the realm of the ICJ, while Japan has more to lose given its current control of the islands. If China continues exploration and resource extraction in the East China Sea, Japan may be more incentivized to stake its claim, however the route of the ICJ leaves too much control to the Court where both China and Japan would prefer some leverage in direct bilateral negotiations.

Theory-Based Interpretation

As articulated by Dino Kritsiotis in his analysis “When States Use Armed Force”, nation states recognize the existence and interpretation of international law and policies, however nations are inclined to treat these laws and policies (particularly those which are not favorable to a nation) as variable and dynamic enterprises, ever changing as the global landscape shifts (Kritsiotis, 2004). In as much, it is the hope of both China and Japan that the international policy institutions, namely UNCLOS in this instance, further refines the areas of contention within the continental shelf definition, or that similar disputes continue to be presented to the ICJ to help establish a more consistent informal international protocol for dealing with continental shelf disputes. It is unlikely that either nation is at all close to utilizing armed force to demonstrate their sovereignty over the islands and shelf area, however since the role of international law has thus far proved to be insubstantial, the potential for armed conflict remains.

There exists no prohibition of violence and little inventive for uncovering non-violent resolution to the disputes, and both nations are unable to follow international protocol because it presents unanswerable questions which impede the progress of negotiations. Paul Kennedy’s “Parliament of Man” introduces the Tennysonian concept that nations can and will destroy one another without some form of global governance, and that there exists a human propensity for conflict (Kennedy, 2007). To minimize the potential for conflict, we must navigate issues independently, and clarify how sovereignty is defined as well as opportunities for collaboration. As the two nations remain entangled in a regional hegemonic struggle (which China is gaining ground on), China seems inclined to operate as a coercive regime, pursuing oil and gas operations in contested waters and limiting the opportunities for joint development projects in the disputed areas. Despite China’s dominance over Japan in terms of production and consumption of gas and oil, the asymmetry of the environment gives Japan little relative power and ensures that China maintain steadfast proclamation over all of the potential resources.

The ‘invisible hand’ has been an apparent force in the dispute, which China increasingly taking its own self-governing actions to pursue economic interests. Historically China struggled to extract hydrocarbons from the East China Sea due to technological challenges, which Japan had an upper hand in. Over time the technological advantages Japan maintained have diminished, and China is less concerned with the establishment of formal cooperation since they are able to move forward independently. Realists might assert that international institutions such as the UN feign objectivity and are only reflections of self-interest and not independent of state behavior, while institutionalists would assert that international organizations can help to change the cultural and social dynamics of the situation and encourage collaboration and resolution as an independent broker. Thus far any attempts to broker a resolution have been muddied in semantics over the definition of the continental shelf and nationalist appeals to satisfy domestic political unrest. Participation in the international institutions has thus far at least played some role in keeping the dispute non-violent, however unless the international bodies can maintain some form of agreeable law and political structure, they may soon become irrelevant in the contest over the islands and exclusive economic zone rights.

Conclusion

The dispute over the islands is critical to providing China with direct access to shipping routes, and a source for purportedly vast quantities of natural gas and oil. The dispute elicits nationalist sentiment from both nations, and Japanese attempts to placate the dispute (notably through the government purchase of the islands in order to remove the potential for activist inhabitation) have only further escalated the disagreement. The ‘status-quo’ ambiguous sovereignty historically allowed the nations to avoid the conflict as it presented a zero-sum game. Neither China nor Japan have opportunity to gain significant advantage, in terms of both hydrocarbons and strategic geo-political leverage. While the discovery of oil and gas reserves markedly complicated the dispute (and by many accounts was China’s only reason for initiating it), the quantity of hydrocarbon resources, which are still largely unmeasured, are only fractions of the quantity of oil and gas that each country expends annually. The claim of sovereignty of the islands is of minimal importance in the disputed hydrocarbons, but rather the dispute over the definition of the continental shelf is the critical element to sustaining Japan’s claim for a median line with China.

The evidence from the United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization provides support for Japan’s claims of sovereignty over the islands through strong and long-standing historical cartographic evidence. However the language from the Conventions on the Laws of the Sea which were developed during the UNCLOS meetings is vague, leaving open the opportunity for legitimate claims by other nation states with continental shelf claims. The nondescript definition and parameters for the continental shelf, in addition to the lack of process for resolving overlapping continental shelf claims presents a significant challenge in addressing the void in international law. Particularly in the East and South Asia region, conflicts over the definition of the continental shelf and associated territory are omnipresent (see Introduction).

The weakness of international law as a means of resolving the dispute is based in the challenge of defining the territorial rights and continental shelf which China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan all have overlapping claims on. It is highly unlikely that the ICJ could arbiter an agreement that could not be reached by settlement between the nations independently, particularly since all nations would have to agree to the findings delivered by the court. While some Japanese assert that elevating the case to the ICJ would result in favorable decisions for Japan, the process of taking the dispute to the Court also introduces the notion that Japan is willing to entertain the possibility of undetermined ownership. If China attempts to introduce the dispute to the ICJ, however, Japan may be more willing to participate in ICJ proceedings (and the onus will be on China to prove its rightful ownership). China is seemingly uninterested in elevating the matter to the Court, both due to the uncertainty in the resulting findings, and the ‘Pandora’s box’ it would open with dozens of other nations which harbor territorial disputes with China.

One proposal to placate the dispute over the islands comes from Kishore Mahbubani, Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. Mahbubani notes that China had accepted Japan’s de facto occupation of the islands for decades while still disputing its sovereignty, however Prime Minister Noda threw off the unspoken balance by purchasing the islands for Japan; China was compelled to respond by virtue of nationalist claim to save face, even if the islands have little economic or strategic geo-political value to them. If Prime Minister Abe wanted to quell the unrest from the purchase of the islands, Mahbubani suggests Japan could ‘sell’ or lease the islands to a private Japanese (or conglomerate) environmental group to dedicate the islands for natural protection, thus ensuring they are undeveloped and uninhabited. This reallocation of the ownership may stymie the escalation of the dispute over the islands, however it does not address the concerns over the allocation of hydrocarbons and economic zones within the continental shelf.

With regard to hydrocarbon production, Japan lags far behind China due to a lack of available resources for extraction. China produces about 4 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, while Japan produces just 3% of this amount (115 billion cf). Consumption of natural gas is about equal between the two countries – around 4.5-5 Bcf each – making both countries net importers of gas. Japan, however, must import over 95% of its gas, whereas China imports a decreasing minority of their gas. With respect to petroleum, China produces 30 times Japan’s petroleum output, has 600x the proven resources, yet total consumption that is just twice that of Japan’s. EIA estimates of the East China Sea suggest there are about 100 million barrels of oil (about 1/50th of China’s current reserves), whereas China’s national estimate is around 100 billion barrels. Using the EIA estimates, the reserves of gas would satisfy just 2/5ths of a year at China’s current consumption rate. With China’s inflated interpretation of the potential resources, their nationalist posturing becomes more understandable and the importance of exclusive economic rights to the sea and seabed resources aligns with their actions since the discovery of hydrocarbons in the 1970’s.

The crux of the dispute remains within the definition of the continental shelf and the geological definition of the Okinawa Trough as interpreted by the international law (UNCLOS and the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf). Both China and Japan have reason to maintain high regard and adherence to international law, though China has significantly more at stake as a result of the number and scale of their territory disputes in the high seas. For these reasons, it is believed that the dispute will continue to be avoided by both nations as neither has well-defined opportunities to gain from an escalation of the dispute. Resolution will not occur through the ICJ, nor will the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf issue any interpretation of the continental shelf in the region while there is still an active dispute between the nations. The most likely resolution to the dispute will be no resolution at all, but a simple deflecting of the problem to a later date, as has been preferred for several decades. The challenges in defining the continental shelf will not be resolved between the nations themselves, and this will require clarification by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to resolve not only the debate beween Japan and China but similar challenges that exist across the globe with respect to understanding the geological definitions for the continental shelf.

Works Cited

Abbott Kenneth W., and Duncan Snidal Why States Act Through Formal International Organizations [Journal]. – [s.l.] : Journal of Conflict Resolution, 1998. – 1 : Vol. 42.

Administration Energy Information East China Sea [Online] // US Energy and Information Administration. – September 25, 2012. – 2 1, 2014. – http://www.eia.gov/countries/regions-topics.cfm?fips=ecs.

Agency Central Intelligence Intelligence Report: The Senkaku Islands Dispute: Oil Under Troubled Waters? [Report]. – Washington, D.C. : Directorate of Intelligence, 1971.

Andreas Hasenclever Peter Mayer, Volker Rittberger Theories of International Regimes [Book]. – Germany : Cambridge Studies in International Relations, 1997.

Kennedy Paul Parliament of Man [Book]. – New York : Random House, 2007.

Klare Michael T. Island Grabbing in Asia [Online] // Foreign Affairs. – Council on Foreign Relations, September 4, 2012. – http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/138093/michael-t-klare/island-grabbing-in-asia.

Kritsiotis Dino When States Use Armed Force [Book Section] // Politics of International Law. – [s.l.] : Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Mearsheimer John The False Promise of International Institutions [Journal]. – [s.l.] : International Security, 1994. – 3 : Vol. 13.

Nye Joseph Parliament of Dreams [Report]. – [s.l.] : World Link 15:2, 2002.

Ramos-Mrosovsky Carlos International Law’s Unhelpful Role in the Senkaku Islands [Journal]. – [s.l.] : U. Pa. Journal of International Law, 2008. – 4 : Vol. 29.

Rongxing Guo Territorial Disputes and Seabed Petroleum Expoitation: Options for the East China Sea [Report]. – Washington, D.C. : The Brookings Institution Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies, 2010.

Shelf Commission on the Limits of the Continental United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea [Online] // Progress of work in the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. – Thirty-second Session, September 24, 2013. – http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N13/485/26/PDF/N1348526.pdf?OpenElement.

SinoShip News SinoShip News [Online] // Wenzhou Bags Another Major Port Investment. – August 05, 2013. – http://www.sinoshipnews.com/News/Wenzhou-bags-another-major-port-investment/3w3c1322.html.

The East China Sea: The Role of International Law in the Settlement of Disputes [Report]. – [s.l.] : Duke Law Journal, 1973.