InnerCity Weightlifting - Policy Brief

Executive Summary

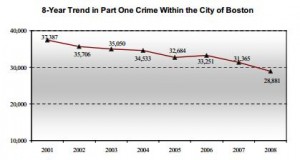

The violent crime among the youth population is an issue being increasingly exacerbated by worsening social conditions, social mobility, and income inequality within the City of Boston. While overall serious crime rates are decreasing on the whole, the youth populations (ages 14-24) have seen increased rates of violent crimes over the past several years.

The increases in violence are often attributed in large part to expansion of gang affiliations and violent communities, exacerbated by widespread firearms (handgun) trafficking and continued drug trade. The City must work to improve cooperative efforts to reduce the crime rates of repeat offenders and proven-risk youth while simultaneously providing improved youth outreach and services to prevent at-risk youth from turning to crime and violence. Without simultaneous efforts, only one end of the overall pipeline is supported.

The InnerCity Weightlifting program (ICW) explored in this analysis provides support to proven-risk individuals in an effort to encourage them to participate in pro-social activities (such as weightlifting) and create a positive sense of community while providing an avenue for growth into legal employment. The program already serves over 100 students on a weekly basis, and could expand to serve hundreds more at-risk students if the resources and foundation for growth were in place. In order to achieve these results and reach more individuals, the program would have to expand its services to reach more communities both by location and across gang lines, a challenge that may require significant outreach and advocacy to prove immediate benefit to the communities. The community opposition may prove the most divisive factor in the future growth of the ICW program, which has found resistance in opening new gym spaces or working in community centers.

If the organization can prove an overall reduction in recidivism of 5% or greater, the financial and social benefits that result (lower incarceration costs, health and community benefits on the order of approximately) will outweigh the costs of the program on a year-to-year basis. The challenges for the program will be to prove the social benefits experienced through the ICW participants to the City and neighborhoods, encourage participation among all demographics of offenders and supporters of the program, and create a long-term financial plan that may include a public investment. The difficulties in producing benefits for the participants include offering pathways for professional development and growth into lawful opportunities, and in creating more positive relationships with law enforcement and government officials and representatives.

With a focus on the positive social interactions and transition into lawful employment, the InnerCity Weightlifting program can generate tremendous social benefit for the at-risk communities and the City of Boston as a whole. Through targeted outreach and advocacy and careful implementation of the program process, these goals can be achieved with minimal financial input and high rates of return.

Violent Crime in Boston

The purpose of this Policy Brief is to detail the purpose, plans, and both intended and unintended effects of the InnerCity Weightlifting program. There are many key initiatives that have worked within the city for many years to address youth violence and gang activity, and the results have been generally encouraging within Boston. For example, after a spike in homicides from 2000-2007, the homicide rate has begun to decline again. Similar trends have been experienced for other violent crimes within the City. The youth population, however, has experienced a rise of violent crime offenses in several key neighborhoods, often attributed to gang-related activity and the increase in availability of firearms.

Through 2012, Part 1 crimes[1] have decreased more than 25% from 2011 levels (1). Youth arrests (16 and under) from 2004 to 2008 were fairly consistent, with almost 800 arrests for Part 1 crimes on average each year (500 violent, 300 property). The number of homicides and rapes decreased slightly, with 1 homicide and 2 rape arrests in 2008 for children 16 and under. Of those 14-24 years of age, Part 1 crime increased from 2,750 in 2004 to over 3,000 in 2008, again with about twice as many violent crimes than property crimes. While overall crime rates have decreased across the city for Part 1 crimes, the youth population has seen either stable or increased violent criminal activity. The flow of guns into these communities and the pervasive nature of the gangs entrenched in the neighborhoods feed into the violent crimes committed across the city, but specifically in 5 key neighborhoods generally situated along the Blue Hill Avenue corridor.

The concentration of crime among youth is highly centralized demographically and by location. Within the youth population, just 1% of students are responsible for over 50% of the gun activity. More than 70% of homicides of those 24 and under were as a result of gang-related activity in the City (80 of 114) (1). Additionally, almost 70% of shootings transpire within 5% of the streets in Boston in these 5 key neighborhoods. The populations committing the violent crimes are from well-documented high-risk communities.

Despite having a lower rate of homicides compared with other cities across the US, Boston still has significant potential to improve the lives and potentials for youth in gang-entrenched neighborhoods communities. In order to break the cycle of incarceration, several organizations have targeted both at-risk youth and individuals who have a criminal history. Programs like Y.O.Unlimited[2], supported by the Boston Redevelopment Authority, work to enable youth to receive their GED, acquire training, and seek jobs or transition to college. The Youth Violence Prevention Coalition[3], supported by the State Street Foundation, seeks to create a network and collaboration of funding sources to address needs in youth programs and prevention initiatives in the 5 most violent neighborhoods along the Southeast Blue Hill Ave corridor.

Many similar programs target at-risk students before they are induced into criminal activities, however there are only select programs and offerings for individuals previously incarcerated or convicted of a crime. The Boston Foundation began the multi-year SafeStreet Boston initiative that is designed to decrease youth violence in a handful of neighborhoods that are disproportionately and persistently affected by violent crimes, encompassing a 3.5 square mile area with high crime and poverty rates. StreetSafe uses local street-level intervention to thwart proven-risk youth from re-engaging in criminal activity through targeted programs and services that promote pro-social behaviors. Upwards of 25 street workers have set out to engage over 2,000 at-risk youth in order to prevent violent offenses. The program integrates support from Boston Police Department, from the City and State legislatures, Boston Public Health Commission, other similar organizations, and the local community members and mentors.

There still remains a great need for providing assistance, community support, and resources for youth development in order to reduce the incarceration rates among high-risk youth in the City. Programs like StreetSafe Boston and InnerCity Weightlifting address the needs of the youth who have already been indicted on violent crime charges, for which there is growing demand as more and more individuals are arrested and released from the MA Department of Corrections facilities. In addition to the programs supporting these youth, continued persistence to break down the contributing factors to criminal activity must be addressed in parallel. Issues such as educational and resource disparities, community-wide legal cynicism, and flow of firearms into high-risk areas must be abated in order to ensure the long-term stability of the region and to decrease pressure on community resources, correctional facilities, and support and development programs such as ICW. Without synchronized efforts to both reduce recidivism and prevent the first crimes from risk-prone youth, pressure on the entire system will continue to grow.

Massachusetts Department of Corrections

The Massachusetts Department of Corrections (DOC) recently released a 5 year strategic plan for 2012-2017. In this report, the DOC predicted an average growth of 2.3% in the male population within prisons, well above the average population growth of under 1% in the state (2). The DOC is experiencing overcrowding of the correctional facilities, and difficulties in retaining costs due to increased health-related issues among inmates. The DOC is already having great trouble in addressing the mental and physical health issues among an increasing population of male and female inmates such as addiction, disease and old age which have strained healthcare costs and resources. Given their estimation of an increased population of incarcerated individuals, the issue of crime reduction must be urgently addressed to decrease the costs burdened on the City and State.

For individuals 20 and under, the (lifelong) recidivism rate was 61.5% in 2002 (3). Males (for all age ranges) have slightly higher rates of recidivism (49% vs 47%), and white criminals have slightly lower recidivism rates than individuals of color (3). Hispanic and Black individuals have recidivism rates upwards of 55%, while white individuals have rates below 45% (3). Rates are higher among those who spent time in a House of Correction or a Community Correction Center, and lower for those who served in State Prisons. The greatest rate of recidivism occurs within the first months after release; the longer an individual can stay out of jail, the more likely he or she is to remain out.

Individuals under 20 years of age are most likely to end up in a House of Correction (75%) or Community Correction Center (20%), and are 60% likely to be convicted of another crime, generally in the first several months after their release. Those who commit property crimes are most likely be reconvicted, while who commit personal crimes or drug-related crimes have lower recidivism rates (4).

Despite lower rates of violent crime across the US and declining property crime rates, the rate of incarcerations continues to grow.

Role of Gangs in Violence

The number of gangs and participating members has increased by almost 4-fold in the past 20 years, with more than 3,500 individuals participating in a gang today across the City of Boston (2). The gangs in the City are highly fluid, with many small gangs operating in similar neighborhoods. The movement around the city of the gangs is significant, while they do maintain areas of comfort and safety. The hierarchical structure within most of the gangs is indistinguishable, like an egalitarian community of individuals committing crimes and offering protection for each other. The relationships between gangs are also highly fluid in many cases.

As the number of gangs and members has increased, the disorganization and unpredictability have made violence prevention difficult for law enforcement. The reduction in crack-cocaine trafficking and on-street drug markets has reduced the amount of crime and gang activity, resulting in more individual-based crimes. Access to firearms gives the gang members powerful weaponry to use against one-another in the streets. This access has transformed youth participation in criminal activity, as the youth are more susceptible to being induced by the use of a handgun. Young students are attending school and walking in their neighborhoods with firearms as a means of protection and for the desired respect and identity they envision it to bring. Firearms are being used in both gang-related feuds and in personal conflicts, with great danger and proximity to the public.

The perseverance of gangs is mainly a function of drug trade in territorial communities. The drug trafficking systems used in gangs are the source of income and funding for gang-related activities, and can lead to violent crimes and incidents in neighborhoods around the city.

Partnership Advancing Communities Together (PACT)

The PACT program is the City’s initiative to prevent violence and identify individuals most likely to be involved in firearm violence. The Boston Regional Intelligence Center keeps a list of individuals that are most likely to engage and be engaged in violent crimes. The majority of these 200-300 individuals reside in the Roxbury/Dorchester/Mattapan neighborhoods. In particular, there are 5 identified neighborhoods[4] which receive priority focus from PACT for community mobilization and violence prevention efforts which including meetings, grassroots door knocking, coordinated gatherings, and violence prevention planning. The objective is to increase access to support programs and health services, and improve the community environment, culture and violence response plans.

The PACT program involves a partnership across the BPD, BPS, Health Commission, Community Centers, the Mayors, Governors, and District Attorney’s Offices, and Youth Services. The program focuses on community policing and prosecution, supervision, and promoting family, education and employment, and a positive community neighborhood. The use of law enforcement data provides a baseline analysis regarding arrests and re-arrests, probation violations, and more. PACT also works to provide support to the individuals through connections to youth services and family, with the intention to reduce violent crime in these neighborhoods. Already, 90% of the identified youth are paired with a youth worker, and targeted outreach is focused on those attending educational and workforce development programs.

InnerCity Weightlifting

Program History

The InnerCity Weightlifting program targets specific individuals and those in need of their services to encourage them to participate in pro-social activities. The initiative is based upon fundamental research in criminal activity. There are high rates of incarceration for violent crimes among those without a high school diploma and those engaged in gang activities. ICW specifically works with the 1% of youth directly responsible for urban crime. Weightlifting’s immediate physical and psychological benefits are of great influence in improving the youth’s attitudes and self-esteem. Weightlifting serves as a common interest to engage and excite the students around a central drive. The reciprocal leadership roles that students take on introduce new students into the program through peer support.

InnerCity Weightlifting is a program pioneered by Jon Feinman which guides at-risk youth and ex-offenders of violent crimes to a life of lawful opportunities. By providing a pathway for success and a diversion from traditional street and gang life, ICW enables and promotes the healthy transition from illegal to legal lifestyles for individuals most at risk. In January 2010, ICW launched with 4 students in a local gym space. In just three months, the program was serving almost 50 students. With one main operating office/gym facility and several satellite gyms around the city, ICW has expanded to serve over 300 students through 2012. Currently, the organization targets about 100 highly-engaged individuals on a weekly to daily basis. In addition to providing gym space for the students to exercise and form a healthy social community, ICW offers professional development, GED tutoring services, and a path towards a personal training degree if that is the route that a student wishes to pursue.

The program bases its needs off of the roots of criminal activity: antisocial behavior, anti-social personality, anti-social peers, and anti-social attitudes. Within the juvenile population, over 44% of arrested offenders are re-arrested within one year of their release. The ICW program addresses these needs by providing a stable and friendly environment for the students to form a community of support within. By taking the youth off the streets and giving them a place to feel comfortable, the program is providing a pro-social environment for nurturing their professional growth and development. The encouragement and support they are able to develop in this setting enables the youth to say no to violence and criminal activity, and examine long-term prospects for their futures.

Through mentorship and coaching relationships, positive peer interactions, workforce development training, and academic support, the program works to reduce recidivism and violence and improve educational achievements, enable employment opportunities, and surround themselves with a community of supportive peers and mentors. The word-of-mouth nature of the program is the main driving force behind its exponential growth; students desire to see their friends succeed and find their path towards success.

Program Goals and Objectives

Reducing Youth Violence and Shifting Community Perspective

The core vision of the ICW program is to reduce youth violence by providing alternate forms of community and pro-social interactions that facilitate positive interactions and healthy growth of individuals. By providing the students with a safe place to be and a healthy environment to thrive in, the program aims to re-structure the stigma against youth violence and spread support systems for the high-risk individuals that are exposed to and incited into violence. Exposure of program successes to the public is instrumental in changing public perspective on high-risk youth and programs aimed at improving recidivism rates.

Reducing Recidivism

One of the program’s core goals is to reduce recidivism among its participants by engaging hundreds of participants around the city and creating a strong network among active students. As of May 2012, the program had recidivism rates of below 20%, well below the 44% average for individuals in this population. The three-year recidivism rate for minimum and pre-release institutions in MA is 34%, and increases to 47% and 62% for medium and high security institutions respectively. The majority of releases to the street are from medium-security institutions (1,300 inmates/yr), where the inmates have almost a 50% recidivism rate over three years.

The reduction in recidivism rates that the ICW program hopes to achieve will result in lower costs to the judicial system and corrections facilities. The financial benefits are analyzed in the Cost-Benefits section.

Professional Development

ICW provides its students with opportunities to grow both physically and emotionally. Equally important to physical health is one’s mental stimulation and growth. In order to achieve this goal, educational development opportunities are made available to the students of ICW through an outsourced GED training program. The inclusion of an educational development program allows students to pursue their GED certifications while also being active members of the gym, improving both mind and body simultaneously. Expanded offerings for professional development in months and years to come include training and workforce development instruction, basic computing skills workshops, and resources for job seeking, resume writing and interviewing.

Through sustained and expanded professional development opportunities, the students that work through the program can continue to build on their successes and transition fully from incarceration to a legal and sustainable lifestyle.

Program Funding

The program is supported through individuals, corporate sponsors, and personal training contracts. By the end of their first 8 months of operation, the organization had grown to over 100 students, with every student referring at least one friend to the program. Corporate sponsors participate in on-site training facilitated by two coaches and two students, and go directly to the earned income streams of the ICW students.

Additional program funding is and will be acquired through individual and corporate donations, multi-year foundation funding and grant acquisition, and the implementation of supported training practices for ICW coaches run out of ICW facilities wherein the coaches donate 20% of earned income from their private practices back to ICW.

Program Expansion and Growth

The program is in just the beginning stages of growth, and long-term goals and evaluations of the program will provide great insight into how recidivism rates and professional growth of the students evolves. ICW plans to operate at 104 students for FY 2013 to further test and refine the organizational model, and to focus on concentrated rehabilitation efforts and long-term financial planning and organization. Throughout 2012-2013, ICW has continued to expand its staff, including coaches and program and operational staff members. In FY 2013, the organization intends to investigate a diversified funding model which includes the earned-income model currently used (where participants pay coaches directly), foundational funding and grants, and corporate sponsorship and participation in on-site training programs.

Since starting in 2010, the organization has expanded tremendously. The model is being implemented on a scale just large enough to gather base statistics from, which can be used as metrics for further program analysis to determine if the rates of reduction in recidivism are in fact worth more than the investments needed to sustain the program model. As the program continues to grow and find success in achieving its goals of improved reintegration into legal citizenship, the question of further expansion and growth will be investigated. Feinman has stated that the organization does not take government funding for many reasons, mainly due to affiliations with the government and trust issues that the students and participants generally have against government entities, however as John Sarvey noted, not many if any programs have grown “to scale” without a certain amount of public buy in or government assistance. It is likely that if the program is deemed successful in nurturing a pro-social environment that has the overall effects of reduced recidivism of its members and improved transition to legal employment, there will be great desire to replicate the model at the city and state scale. An “at scale” approach is analyzed in a following section that serves to outline how this growth may occur.

Consequences of the Program

There are many potential intended and unintended consequences of the InnerCity Weightlifting program. It is intended that the model will decrease recidivism rates, improve transitional job opportunities, and in turn have significant financial and community benefits that result with these two objectives.

Some potential unintended consequences may include an increase in gang activity or violent crime in the gym neighborhoods, increased reliance and dependence (pressure) on the program which could create unsustainable strains, issues of legal cynicism (trust of law enforcement), and further exacerbation of gang-related conflicts. The underlying issues of gang activity and violent crime are also a crucial factor in determining how the ICW program proceeds to achieve its goals in these high-risk communities. Unless the contributing factors can be addressed, there will continue to be more and more convicts and high-risk youth that require support from ICW and similar programs.

The “Not In My Back Yard” attitude is one often associated with programs affiliated involving potentially-dangerous side-effects. Neighborhood residents often oppose facilities that could result in perceived adverse effects to their community, and the ICW program has already encountered difficulties in growing their program as a result of pushback from the community.

The participants in the ICW program have had mainly negative experiences with law enforcement and the judicial process, and have very high legal cynicism. To combat these doubts, the ICW program may want to investigate how to integrate the police and law enforcement representatives into the program in order to slowly improve relationships and understanding on both sides of the relationship. A positive interaction and rapport with law enforcement and public support can provide a new foundation for the youth transitioning into lawful lifestyles.

Adverse social and demographic biases may also be experienced, as the program generally accommodates Black and Hispanic participants that provide personal training services to the more affluent White male population. ICW should be conscientious of potential perceived racial implications and stereotyping by actively recruiting White participants and Black and Hispanic sponsors to take part in the workouts and training sessions.

“Not In My Back Yard”

The common theme that InnerCity Weightlifting and similar organizations face when looking to grow the organization is the “not in my back yard” mantra a community assumes when a perceived negative impact to their area presents itself. In theory, most any and every individual from a community would be in support of a well-run, beneficial program that keeps high-risk individuals out of potentially dangerous situations through positive interactions. When ICW looked to open up their first facility on B street in South Boston, they were met with heavy community opposition that ultimately forced them to back out. The community members spoke out against ICW moving in to the community, citing the “importing of criminals” into a community that is generally safe. With this feedback in mind, Feinman revised the proposal to include outreach to the South Boston community in particular in order to make the program more beneficial for the immediate community area (1). Still, opponents to the inhabitance were steadfast in their doubts against the organization’s safety.

The residents in the surrounding neighborhood believed that, by allowing these individuals to come exercise on their block, the potential for criminal activity and dangerous interactions would increase by an amount greater than the perceived benefit of providing this community space. Surely if the building were in another neighborhood, one would expect these individuals and representing city councilmen to be in full favor of the program.

There are many preconceived notions involved in the immediate reactions that the community members hold when they are informed that a program such as ICW is looking to move into their neighborhood. Without any prior knowledge of the participating individuals, the community passes judgment that deems these individuals unsuited for being in their neighborhood. In reality, the ICW participants need to get off of their streets and neighborhoods in order to leave behind the crime and lifestyles that predicated their prior mistakes. When the youth are not enabled to ‘get off their block’, they are trapped in the system which caused them to turn to illegal lifestyles and gangs in the first place. In order to establish a sustainable and nurturing community needed for the ICW program, the students must feel that they are in a safe environment both physically and socially. This requires not only physical separation from their existing conditions, but also social conditions that support emotional well-being. If the community does not support the program and actively disputes their existence, it could be difficult for the participants to feel “at home” and in an appropriate environment.

Feinman explains that the individuals they work with in this program are men of substance, citizens who do not wish to go to jail (again) and are searching for an appropriate avenue to propel them out of the vicious cycle of incarceration. The students, he asserts, make logical decisions based on the circumstances that they are in and the opportunities they have been provided. If they are afforded an opportunity to grow in a healthy environment, they will pursue it with vigor. If they are forced to exist in the conditions that implicated them in dangerous interactions, they will be much more likely to continue to be associated with dangerous and illegal activities.

Legal Cynicism

Many individuals that have been raised in high-risk areas have had generally negative interactions with law enforcement, and in turn do not have positive attitudes towards the legal system and police in particular. The legal cynicism that develops from these interactions and persists in youth from an early age is a main contributing factor in the low rates of criminal convictions (“closed cases”) and in exacerbating criminal activity. The communities in the high-risk areas have a generally negative view of law enforcement, and are traditionally uncooperative in criminal investigations and efforts to break down existing gang networks, usually due to fear of consequences from ‘snitching’ on their neighbors. The ICW participants noted extremely high legal cynicism among its participants, after having experienced the incarceration system and the legal ramifications that result from criminal convictions. The ICW members noted the dangers in cooperating with the police, namely that of putting themselves and their families at risk of retaliation. Without the trust of police and the legal system as a whole, high-risk youth and communities will continue to be uncooperative which will likely have self-damaging effects on the community; as violent crime offenders are allowed to walk free due to lack of testifying witnesses, they will continue to commit crimes and entrench their communities in violence.

The Underlying Issues

There are many well-known contributing factors that have exacerbated the difficulties of living in the areas identified previously as those with the highest rates of violence. These underlying issues must be addressed in concert with the violence prevention and recidivism programs aimed at reducing current crime rates in order to ensure long-term positive growth of these communities. Without parallel constructive efforts to address these factors, the rates of violence and incarceration in these communities will only continue to increase.

One of the main contributing factors is the pre-K and K-12 educational system which serves the high-risk communities and youth. The resources within these schools are deprived of funding and infrastructure, and as a result the students are not receiving the education and childhood development necessary to provide them with the life and workforce skills that are required for a healthy and self-sustaining future. Another of the main factors in violent crime incidents stem from drug-related conflicts. The drug trafficking systems provide funding to gang organizations and induce significant crime and violent interactions. Other factors that create further imbalance include lack of community resources and overall community efficacy, access to healthy food options, and services for troubled and high-risk youth.

The importance of addressing both contributing factors and existing conditions are equally important in lowering current crime rates and in ensuring long-term reductions in violent crime in the City of Boston.

Costs and Benefits

To determine the costs and benefits of the program, the operational budget of the organization is used as the expense and the benefit is calculated as a function of the reduced recidivism rate and costs of incarceration. A projection through FY 2015 is calculated below. There are several variables that must be investigated in order to create a more functional model of the social benefits and Cost/Benefit ratio, including:

- Demographic information

- Age, Gender, Home Location, Race

- Crime committed and related incarceration length

- Prior recidivism incidents

- Average incarceration period for recidivism incidents

- Location of Incarceration (Community Correction Center, House of Correction, State Prison, Federal Penitentiary)

- Availability of additional programs, community support, and resources

- Employment after release

The Benefits of Recidivism Reduction analysis below offers a preview of how the social benefits of the ICW program could be calculated, given more information regarding the participants and the average recidivism incarceration statistics.

Costs of Crime to Society

The basic cost of crime includes the costs incurred by the victims (property, medical expenses, opportunity costs, and emotional suffering), costs to the criminal and justice systems (police, courts, and correctional facilities), and the opportunity costs to the perpetrator.

The cost to society of recidivism incidents is equal to the amount of money required through taxation to pay for the prosecution and incarceration of criminals. More than 90% of these costs are paid by the State and Local governments through the local and state level correctional facilities and judicial systems (5). Nationally, the cost of incarceration for one year is approximately $25,000 while the cost for incarceration of a criminal in Boston is approximately $45,000 a year (5) (6).

Traditional policies for reducing crime rates and thus reducing the costs of crime are increasing the presence of police enforcement and increasing the severity of criminal activity. Both of these pathways incur additional costs in the form of man-hours required to arrest and processes additional criminals, with the intended consequence of lowering the more long-term crime rates.

Benefits of Reduced Recidivism

A reduction in recidivism has several benefits to society. The immediate financial benefits are a result of lower incarceration costs and lower judicial costs. As the recidivism rate declines for a community over time, this is reflected also in lower requirements of the police force and judicial system, which can reduce government spending. Lower recidivism rates will likely also have long-term health benefits to the community and result in lower emergency room visits and improved health of community members. Criminals have traditionally high rates of unemployment due to difficult in acquiring legal employment, and in turn a lower recidivism rate will likely reduce overall unemployment among this population and lead to lower unemployment expenditures.

Baseline Scenario

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

||

|

COSTS |

Operation Budget |

$480,000 |

$680,000 |

$850,000 |

$1,000,000 |

| Students Served* |

104 |

104 |

150 |

150 |

|

| Cost per Student |

$4,615 |

$6,538 |

$5,667 |

$6,667 |

|

|

BENEFITS |

Average Recidivism Rate |

50% |

50% |

50% |

50% |

| ICW Recidivism Rate |

20% |

20% |

20% |

20% |

|

| % Reduced Recidivism |

30% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

|

| Average Cost of Incarceration (yr) |

45,000 |

45,000 |

45,000 |

45,000 |

|

| Average Length of Incarceration (yr) |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

| Benefit per Student |

$6,750 |

$6,750 |

$6,750 |

$6,750 |

|

| NET COST/BENEFIT RATIO |

1.4625 |

1.032353 |

1.191176 |

1.0125 |

|

| *This figure does not include coaches and other staff at ICW | |||||

The above chart assumes an average recidivism rate of approximately 50% for non-ICW participants, 20% for ICW participants, and an average length of incarceration of 180 days (1/2 year). These assumptions can be adjusted to more properly fit the values attributed to the populations in consideration. This baseline set shows that a program with average costs to participants under $6,750 will produce positive social benefits in the form of reduced incarceration costs. As the average length of incarceration from a recidivism incident increases, the benefits of the ICW program become very high.

Adjusted Scenario

The average inmate length of stay in Massachusetts Department of Corrections facilities is over 4.5 years, which costs the DOC over $200,000 per inmate. If this length is considered, and only a 10% recidivism reduction results from participation in the ICW program, the cost/benefits are even greater as displayed below:

|

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

||

|

COSTS |

Operation Budget |

$480,000 |

$680,000 |

$850,000 |

$1,000,000 |

| Students Served* |

104 |

104 |

150 |

150 |

|

| Cost per Student |

$4,615 |

$6,538 |

$5,667 |

$6,667 |

|

|

BENEFITS |

Average Recidivism Rate[1] |

40% |

40% |

40% |

40% |

| ICW Recidivism Rate |

30% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

|

| % Reduced Recidivism |

10% |

10% |

10% |

10% |

|

| Average Cost of Incarceration (yr) |

45,000 |

45,000 |

45,000 |

45,000 |

|

| Average Length of Incarceration (yr) |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

|

| Benefit per Student |

$18,000 |

$18,000 |

$18,000 |

$18,000 |

|

| NET COST/BENEFIT RATIO |

3.9 |

2.752941 |

3.176471 |

2.7 |

|

| *This figure does not include coaches and other staff at ICW | |||||

If the adjusted scenario proves more accurate given the conditions of the incarceration system and the effects of the InnerCity Weightlifting program, than there exist great benefits in investments for the ICW program.

Break-Even Scenario

With the length of incarceration of 4.5 years at a cost of $45,000 per year, the reduction in recidivism could be as low as just 4% (benefit of $7,200 per person) to still be greater than the costs of the program by Year 5 ($6,667 per person). If ICW can produce an overall reduction in recidivism of greater than 4%, the costs of the program should be lower than the benefits produced through lower incarceration expenses. The program will have good ability to calculate the recidivism rates of its participants, however the difficulty in this analysis then becomes the accurate calculation of recidivism rates among the “control” or comparison population. The low percent required reduction in recidivism makes this calculation seemingly unnecessary, as the complications in determining an accurate rate may be overwhelmingly difficult (for reasons detailed above). A 5% reduction in recidivism can be used as a baseline goal by which the organization guarantees its social benefits far exceed the costs required.

Works Cited

1. Department, Boston Police. Crime Statistics. [http://www.cityofboston.gov/police/stats/] Boston : City of Boston, 2012.

2. Office, US State Attorney’s. The Boston PACT Program. District of Massachusetts : US Attorney’s Office. http://www.justice.gov/usao/ma/violentcrime/BostonPACT.pdf.

3. Corrections, Massachusetts Department of. Strategic Plan: 2012-2017. Boston : MA DOC, 2012. http://www.mass.gov/eopss/docs/doc/research-reports/strategicplan-03-12-12.pdf.

4. Feinman, Jon. InnerCity Weightlifting Still Awaiting City Permit for South Boston Gym. s.l. : Boston.com, October 26, 2011.

5. Commissoin, Massachusetts Sentencing. Comprehensive Recidivism Study. [http://www.mass.gov/courts/admin/sentcomm/recrep060102.pdf] Boston : s.n., 2002.

6. Corrections, Massachusetts Department of. A Look at the Department of Correction Pre-Release Facilities. [http://www.mass.gov/eopss/docs/doc/research-reports/briefs-stats-bulletins/inmate-pre-release-brief.pdf] Boston : Office of Strategic Planning and Researc, 2011.

7. Research, Center for Economic and Policy. The High Budgetary Cost of Incarceration. 2010. http://www.cepr.net/documents/publications/incarceration-2010-06.pdf.

8. Corrections, Department of. 2011 Annual Report. s.l. : MA Department of Corrections. http://www.mass.gov/eopss/docs/doc/annual-report-2011-final-08-01-12.pdf.

[1] Homicide, Rape, Robbery, Aggrevated Assault, Burglary, Larceny, Auto Theft

[2]www.bostonredevelopmentauthority.org/yoboston/en/offering.asp

[3] http://bostonyvpfunders.org/

[4] Orchard Park, Grove Hall, Uphams Corner, Bowdoin/Geneva, and Mattapan

[5] The average rate for Male recidivism across all ages in the State is 44%, and over 60% for individuals 20 and under (8)