Download PDF: Transitional Bilingual Education in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

April, 2013Executive Summary

There are dozens of challenges facing the Nation and State’s educational systems – rising education costs (driven in large part by healthcare costs), outdated infrastructure and technology, changing standards, curriculums and pedagogical models, and the social, cultural, and economic hurdles that make the education of each student distinctively demanding. It is the challenge of the district’s teachers and staff to best utilize their resources in delivering the highest level education to all students. In an average classroom with generally just one teacher and upwards of 20 students, preparing and delivering a lesson – particularly anything engaging – is a challenge in and of itself. Of the daily tasks many urban district teachers must conduct, educating students with little to no English capacity is uniquely challenging – but manageable and even beneficial, given the right resources and class structure.

Massachusetts’ educators are, in general, poorly prepared to provide the same quality of instruction for proficient English speakers as they are for students who have very low English capacities, despite the minimal training for ELL/ESL education. However, there exists significant social and economic benefit in nurturing and supporting the wide diversity of languages spoken by the 200,000+ MA students that have an alternative primary language. For both the improved educational capacity of these students in future years (and potentially lower long-term costs), and the broadened intellectual capital that it supports, it is critical that the State make a concerted effort towards rewriting the standard model and options for education English Language Learning (ELL) students.

The 2002 Ballot Question 2 in the Massachusetts mid-term elections, and the public vote that approved its passage, marked the end of the Nation’s first state mandated transitional bilingual education plan (passed in 1969). Over the past decade since its passage, public schools have been compelled to immerse non-English speaking students into a generally one-year sheltered English immersion (SEI) program to instill proficiency, after which they are placed directly into mainstream classes. From a student’s perspective with little to no English capacity, learning in this environment is a frustrating (and often overwhelming) test of patience and social contextualization. From the teacher’s perspective (who generally has no bilingual skills), it’s a great personal struggle to make sure the range of students are able to understand the content but are simultaneously not stifled from learning at their capacity.

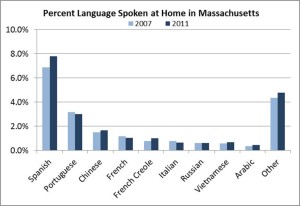

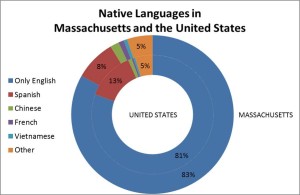

The non-English speaking population in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts has been growing for several decades, with fully 1 in 5 speaking a language other than English at home in 2011 (1). Of the many languages, Spanish is the most widely spoken; there are about 1 in 12 that speak Spanish today, just over half of which can speak “very well”, and half “less than very well” (1). There was a 16% growth in the number of Spanish-speaking residents from 2007-2011, an increase of more than 65,000 residents in just 4 years (2).

Of the 220,000 K-12 students in households that speak a primary language other than English, about half (102,500 students) speak Spanish at home while about one-third speak speak another Indo-European language (2). The other 15% speak Asian languages or another language (5%) (3). 10% of these students grow up speaking only English in a non-English speaking household, thus losing the intellectual capital and lingual history of their family (1).

Compared to the United States, Massachusetts has a slightly lower percent of Spanish-speaking residents; in the US, there are about 13% native Spanish speakers, compared to about 8% in Massachusetts. As the demographic in the Commonwealth continues to shift towards an increased diversity of languages and cultures, reflective of that in the US, the Commonwealth must embrace the social and lingual range, and the intellectual capital that these resources can provide.

In order to nurture and support the growing population of non-native English speakers, the Commonwealth must support the education of our youth in both English and their native language(s), as well as provide bilingual opportunities for all students. A well-supported public school system with a transitional bilingual education model can not only nourish the linguistic capital in the State, but also provide a backbone for long-term, sustainable multi-lingual education in our K-12 public education system. A peer-mentorship initiative, coupled with parent and community support in school classes, can self-sustain a strong multi-lingual program through the entire K-12 system. (1)

In order to nurture and support the growing population of non-native English speakers, the Commonwealth must support the education of our youth in both English and their native language(s), as well as provide bilingual opportunities for all students. A well-supported public school system with a transitional bilingual education model can not only nourish the linguistic capital in the State, but also provide a backbone for long-term, sustainable multi-lingual education in our K-12 public education system. A peer-mentorship initiative, coupled with parent and community support in school classes, can self-sustain a strong multi-lingual program through the entire K-12 system. (1)

Several key legislative initiatives before the House and Senate in Massachusetts stand to reform the standards and operating models for schools providing education to English Language Learners. These Bills would: allow for school districts with low English proficiency rates to adopt alternative ELL education models; establish standards and testing mechanisms for evaluating and monitoring performance; create infrastructure within the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education to support bilingual programs; create potential funding sources for schools implementing alternative ELL education models; and provide all students (not only ELL students) with the opportunity to be recognized by their district and State as having achieved dual language proficiency – an increasingly valuable and demanded resource in the workforce. Instead of squandering the potential for all students to be able to embrace multiple languages (as the current SEI program does), these initiatives would support the growth of a practice-driven educational model to sustain the growth of students in multiple languages.

History of Bilingual Education

Bilingual Education In the United States

In the 1927 Farrington v. Tokushige Supreme Court ruling, the judges elected that it violates the Fifth Amendment to prohibit a school from teaching in a language other than English (4). A 1949 case deemed again in support of bilingual education, affirming that parents have the right to have their children taught in their language of choice. In 1964, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act allowed for funding to be withheld from schools that maintained segregation and thus did not recognize the need for multilingual education.

Public groups during the Civil Rights movement fought in favor of the recognition of language rights and education, and the increased population of foreign residents and students pushed Congress to pass the Bilingual Education Act in 1968 (Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act [ESA]) (4). The law encouraged school districts to offer bilingual programs through new pedagogical models by providing funding programs that targeted low-income and non-English student populations. The Federal initiative was implemented in order to meet the needs of low-proficiency students and support the schools in offering these services, mainly in the form of transitional bilingual education.

In 1974, the Act was amended to define bilingual education programs by identifying goals and determining feedback mechanisms for evaluating the program effectiveness. The amendment also broadened the reach of the program eligibility by eliminating the low-income requirements in the original Act in 1968 (4). Following the Act, the Supreme Court decided in the 1974 Lau v. Nichols case that “it was the school district’s responsibility to provide the necessary programs and accommodations to children who did not speak English” (4). The Court did not address the question of a constitutional right to bilingual educational assistance or education. As the “Lau Remedies” expired, the 5th Circuit court established three rules for “appropriate action” to qualify for providing the necessary program: sound educational theory, sufficient resources and personnel, and proven effectiveness (4). The broad requirements resulted in a wide range of program models for ELL students.

President Reagan campaigned for “back to basics” education that disenfranchised non-English speaking residents. The case against bilingual education claimed the programs were ineffective, however the results of the programs have conflicting interpretations. Under Clinton’s presidency, the Improving America’s Schools Act reauthorized Title VII and the development of bilingual capacity as a national resource. Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act then reauthorized the ESEA, and imposed testing measures that favored the use of English-only instruction (4).

By 2010, there were 4.7 million ELL students in the Nation, equating to about 10% of enrolled children (5). The majority of ELL students are in fact born in the United States – more than two-thirds at the elementary level. A majority of the ELL students are Hispanic; almost 40% of all Hispanic fourth grade students are in an ELL program, compared to about 20% of eight grade students (6). Of these students, the majority exist in specific geographic communities, mainly in the states of California, Texas, New Mexico, Nevada, and increasingly in Massachusetts. An Urban Institute investigation discovered that about 70% of ELL students are educated in just 10% of the nation’s schools.

Bilingual Education In Massachusetts

Massachusetts established the first state-mandated transitional bilingual education program in the US in 1969, amid the furor of desegregation efforts. In 1993, the State established the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) to evaluate student performance and aptitude, including English literacy and vocabulary aptitude.

The mid-term elections in 2002 included a ballot referendum question regarding the application of bilingual education programs in the State: “English Language Education in Public Schools”, Question 2 (7). The question, a prerogative of Ron Unz and the “English for the Children” campaign, asserted that ELA education in MA had failed to provide adequate education for non-English speaking students, but that an English-only classroom mandate would acclimate students to the English language faster. After the referendum was passed, the transitional bilingual education model was replaced with 1-year sheltered English immersion programs. The law also required these students to participate in the Massachusetts English Proficiency Assessment (MEPA). The tests have had arguable effects at ensuring accountability, and have generally created a more test-driven curriculum that does not provide the real-world connections for preparing students for their futures.

The ELL law passed in 2002 did not require teachers to have any additional certification to teach ELL students, and have conflicting information from the State, Districts, and school administrations on how SEI classes should be taught. Educators are quick to realize how difficult it can be to teach students who have low or no English proficiency without using their native language. Often times when teachers do not provide translations for vocabulary beyond a student’s comprehension, the student is forced to seek help from classmates or fall behind in their work.

The current system requires that foreign or other non-native English students spend just one year in a sheltered immersion program, however it is evident from years of ELA education that English is a language that takes many years to reach proficiency in; generally 4-6 years are required for even young students to become proficient in a second language (4) (8).

About 70% of residents voted in favor of Question 2 to eliminate transitional bilingual education, which generally seemed to have been a reflection of the residents’ socio-political attitudes and prejudicial anxieties related to the use of languages other than English. Without the knowledge of pedagogical models for educating ELL students, the challenge of making such a critical decision should not have been left to the general public. Whereas 93% of Latin American residents voted against Question 2, the students and families most affected by the decision, it was the predominately-Caucasian population that accepted the new pedagogical model. The politicization of the issue and over-simplification to the public turned ELL student education on its head, and has left educators stranded without resources to teach their non-English native speakers.

In 2011, the Justice Department declared the MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education had been in violation of the Equal Educational Opportunities act due to the continued failure of the ELL students to gain proficiency at or near the rates of the general student population. The failure to “take appropriate action to overcome ELL students’ language barriers” was remedied by the requirement for teachers in SEI settings to receive additional training in ESL teaching (previously a voluntary training).

According to the 2012 MCAS results, a full decade after the law eliminating transitional programs, the ELL students still have proficiency rates 50% and 80% below the rates of traditional students. These differences are most notable in science and math courses, where ELL students score at a rate of as low as 1/5th that of traditional students (9).

Current Legislative Initiatives for Bilingual Education

On January 22nd of 2013, several education-related Bills were referred to the Education committee and scheduled for hearing at the beginning of April. These Bills are generally designed to loosen the restrictions of SEI requirements and improve the long-term social and economic benefits of language diversity and proficiency.

The House Bill 479 sponsored by Representative Sanchez supports the implementation of an Act Relative to Enhancing English Opportunities for all students. This Act would redefine the interpretation for ELL programs in order to allow for greater mobility and choice for districts in how they deliver and evaluate their educational models for English learners, including transitional bilingual education and two-way bilingual education. The Act also establishes several reporting mechanisms and standards for tracking the students and services administered. The House Bill 425 sponsored by Representative Holmes also supports the implementation of a wide range of tools for supporting and evaluating school progress in narrowing the education achievement gaps.

The Bill put before the House and Senate in April of 2013 by Representative Walz and Senator Spilka (H.533 and S.270) have set forth a Dual Language Education Programs Act that would set up a Dual Language office under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of Education in the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education that will monitor, evaluate, and provide assistance and resources to districts and schools implementing bi-lingual programs. Additionally, a bi-literacy recognition for students attaining proficiency in multiple languages will be institutionalized to accredit students who meet the qualifications for proficiency in more than one language. The Dual Language Education Programs Act would serve to unify and disseminate information on the bilingual education efforts in the Commonwealth, and provide bilingual students with an opportunity to leverage their linguistic capital when seeking employment or higher-education opportunities.

Bill H.353 sponsored by Representative Cabral would establish an Act to Close the Achievement Gap for English Language Learners. The Act would enable school districts’ superintendents and commissioners to establish alternative ELL programs for schools with limited English-proficient students. The programs would be implemented at the discretion of the schools, and would be able to be continued if proven successful in improving proficiency rates for the school.

House Bill H.327, sponsored by Representative Andrews, seeks to pass an Act to Improve Global Competitiveness through Additional Language Competency. The Act would require the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education to develop standards and learning objectives for all students pre-K to 12th within the existing foreign language framework/curriculum, while also identifying resources to support the schools in achieving these standards. The Act also introduces the possibility of including a foreign language component of the MCAS exams in which students could prove their proficiency.

All of the aforementioned Bills complement each other in the establishment of a standards-based, quantified educational plan for bilingual learners which would establish a certification process that provides students with the opportunity to put their bilingual skills to their advantage.

The passage of each of these Bills is instrumental in furthering the State’s capacity for educating ELL students and ensuring long-term vitality and intellectual capital for the Commonwealth. Perhaps most important is the passage of the H.353 Bill to Close the Achievement Gap for ELL Students. This Act would allow for schools to develop alternative educational models for their ELL students in conjunction with or in place of the existing SEI programs. By allowing each district to define and implement the models which suit them best, the districts and the Commonwealth are more likely to see long-term growth and increased proficiency rates for ELL students. The most-widely recognized model beyond the SEI program is that of Transitional Bilingual Education.

Transitional Bilingual Education

The transitional bilingual education model allows for ELL students to participate in a multi-year transitional program to ease them into English literacy while maintaining continual support through content courses such as math and science. Students generally perform better in content-related courses when they participate in a more long-term, sustained transitional education model instead of a sheltered one-year immersion experience (4) (8). With sufficient resources and materials to support the instructional needs of ELL students, a transitional bilingual model can support stimulating content and language activities to promote student growth in English proficiency and general content knowledge.

One counter against a transitional program asserts that the development of a second language occurs faster when immersion is stronger, as is the case with an SEI-style program that is almost entirely taught in English. From 2007 to 2011, the English proficiency for native Spanish speakers has improved only very marginally. The population of Spanish-speaking residents has increased significantly over the past few decades, and through the past several years in the second-half of the decade’s experience with the SEI program, the English proficiency for native Spanish speakers has remained just above 55%. Further, after 7 years of using the SEI program in Boston Public Schools, only about 50% of Hispanic male students manage to graduate from high school within four years (4).

It is crucial to re-establish and refine the program requirements and standard procedures for a transitional bilingual education model, including a reanalysis of the monitoring and evaluation metrics that must be used to evaluate the successes and failures of the programs. The curriculum materials (multi-lingual texts and supporting curriculum components) and the in-class resources (intellectual and lingual capacities of teachers and volunteers) must be embraced and sustained in order for the transitional model to maintain success. Additionally, the peer-mentoring structure and community support model serves to add further long-term stability to the transitional model by making it easier for teachers without linguistic content knowledge to still provide an environment for all ranges of students to excel.

The debate over Sheltered Immersion and Transitional Bilingual education is both long-standing and well-argued in both circumstances. As with many similar educational outcome studies, data can be drawn to support and refute both types of programs. And as is the case with many educational initiatives, the effects on students are by and large determined by the effectiveness of the teacher and the availability of support, resources, and materials to reinforce the content.

As Governor of the Commonwealth, it is important to support the rights of districts to choose the educational models for ELL students as they think most suitable for their particular students. By binding districts to the SEI model, teachers and paraprofessionals are forced to work around the rules to reach some students through their native language. In other cases, ELL students just don’t have access to the teachers and resources required to help them understand English without transitional support. The result is what we have today: a still-struggling ELL student population, and disenchanted and challenged educators.

Implementing Bilingual Educational Models

It is critical that any attempt to support Bilingual Educational models above and beyond the current Sheltered Immersion Experience are well-supported and defined such that administrators, teachers, and students and parents are all understanding of the process for ELL students interested in the program. This does not necessarily mean an increased requirement for funding, however there must be some investments made to establish the Dual Language office in the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, and to allow for supporting staff (that generally already exist) at schools with high rates of non-native English speakers.

By allowing districts to define and implement alternative ELL programs as seen fit, the State will be able to quantify and qualify how the different programs have an impact on the student proficiency rates. Using this information over the course of several years, the establishment of best practices and programs can be conducted and the resources and findings shared with other districts and schools through the DESE. In many instances, the intellectual resources (in the form of bilingual teachers and paraprofessionals/staff) already exist, at least to a minimal extent, in schools where there are high rates of ELL students. The change would be mainly to the pedagogical models and teaching procedures for the educators and staff members that support them; by allowing teachers to embrace the alternative language skills of ELL students, the students can support each other and the teachers can bring previously inaccessible English content into terms which ELL students can interpret and comprehend.

The bilingual education model can be supported by a peer-mentor structure in which more-advanced ELL students can aid less-proficient students in a mentorship capacity which not only improves the sense of community and school-pride but also simplifies the teachers’ role in the translational requirements (which are often out of capacity for non-bilingual educators). In schools that adopt full bilingual programs for all students, the peer-mentor program can pair students learning Spanish with students learning English and proficient ELL students in order to support the lingual growth of all parties simultaneously in a mutually-beneficial relationship.

The costs for bilingual education can be higher than the standard SEI models, since they generally require more paraprofessional staff or bilingual educators, which are generally hard to find – especially in content-driven courses such as math and sciences. A 2008 New York Immigration Coalition study found that can require up to twice the normal per student expenditure for ELLs (5). In exchange for increased expenditures for students (generally in elementary and middle school years), the districts and teachers would be able to achieve higher proficiency rates for students and in turn simpler and less-costly secondary education. The improved transition would allow for higher student retention among the ELL student population, those most likely to drop out before graduation. The State would also realize long-term benefits in supporting bilingual students and residents due to the increasingly global society in which we live, and the nature of the evolving multilingual economy and market.

In addition to the peer-to-peer mentorship program, it is imperative that the Commonwealth leverage the intellectual support of the community and higher education institutions. In Boston in particular, but also in cities like Worcester and Lowell, the predominance of a strong higher education community enables K-12 public institutions to tap in to the support of these students. Higher Ed students are increasingly interested in civic engagement and K-12 support in many forms and capacities – from out-of-school and after-school support to in-class content assistance. Targeted intervention efforts in specific schools and in collaboration with Education students, Spanish Language students, and STEM students have the capacity to greatly support the needs of K-12 teachers and students.

Works Cited

1. Bureau, United States Census. Language Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English – 3-Year ACS. [http://factfinder2.census.gov/] s.l. : U.S. Department of Commerce, 2013. B16001.

2. —. Language Spoken at Home. s.l. : U.S. Department of Commerce, 2013. S1601.

3. —. Age by Language Spoken at Home – 3-Year ACS. s.l. : United States Department of Commerce, 2013. B16003.

4. Nieto, David. A Brief History of Bilingual Education in the United States . Boston : Perspectives on Urban Education, 2009.

5. Armario, Christine. US Bilingual Education Challenge: Students Learning English as Second Language at Risk. Huffington Post – LatinoVoices. April 2013.

6. Progress, National Assessment of Education. 2011 National Results. Washington, D.C. : NAEP, 2012.

7. Commonwealth, William Francis Galvin – Secretary of the. 2002 Information for Voters: Question 2. Boston : Secretary of Commonwealth, 2013.

8. F., Genesee. Program Alternatives for Linguistically Diverse Students. Washington, D.C. : US Department of Education, 2005.

9. Sun, Lowell. Bilingual Ed’s Return is Not the Answer. Lowell Sun Online. 2013.